The 5-Step Pizza Pump and Dump

Why it doesn’t matter if the story is true—just that it looks true.

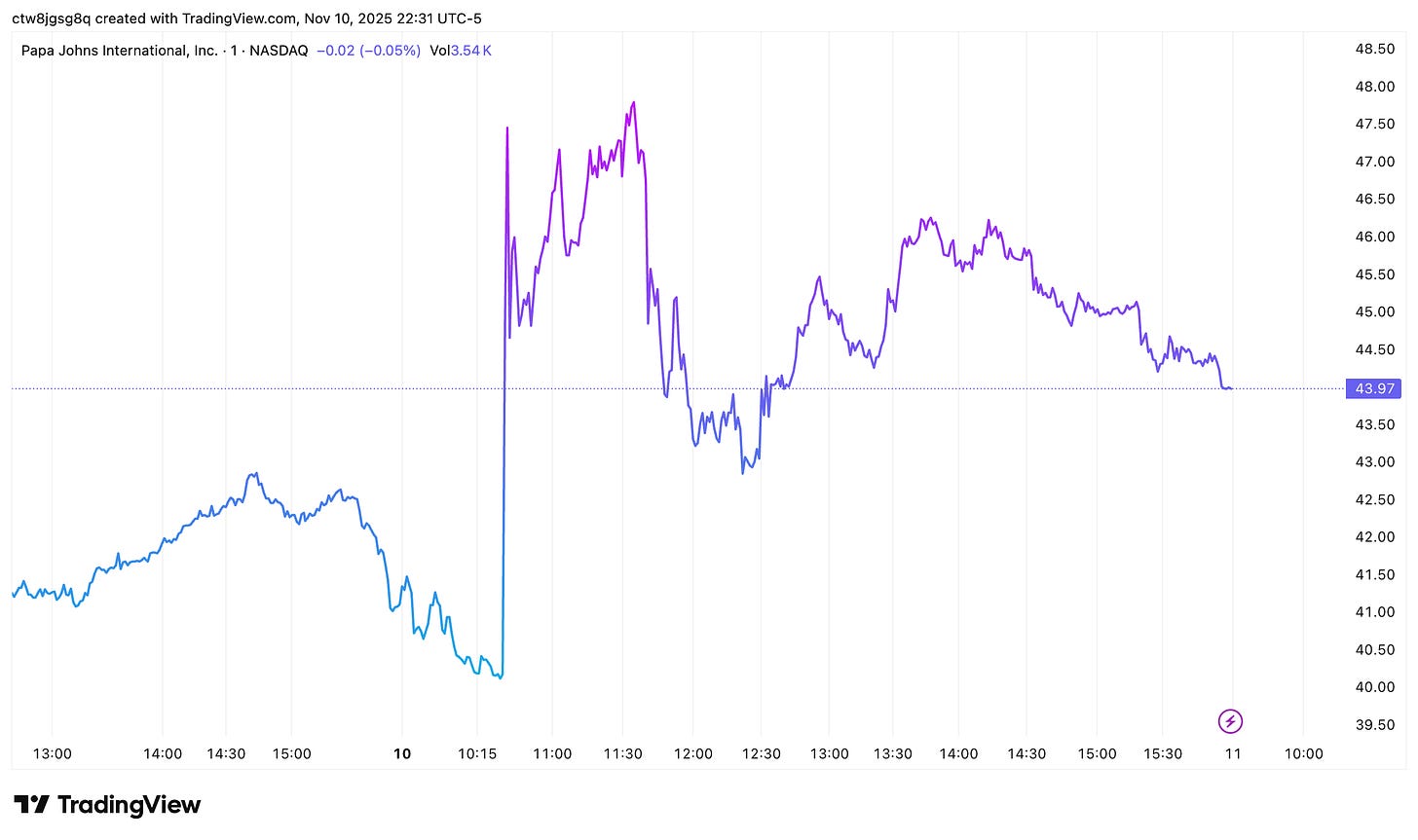

On Monday morning, Papa John’s stock jumped 13%.

The reason: a report that a private-equity firm was buying the company for $65 a share, or about $2.7 billion.

That’s exciting because Papa John’s shares were trading around $40, and 65 is, well, more than 40. That’s a $15-per-share difference; free money, if the deal is real.

But there was no press release from Papa John’s. No SEC filings. No quote from the company.

Just…internet headlines, which is kind of how rumours start these days anyway. So, people started buying.

Step 1: Cement the Headline

The story began on a British website called BusinessMole, which cited another site, NewsReleases.co.uk—a place where you can “get featured” by, well, paying them.

Then ABC Money ran with it.

ABC Money, as you might guess, is definitely not ABC News. It is a small, possibly-bankrupt UK company whose logo looks suspiciously like ABC News’s logo, and whose “journalists” have headshots that are stock images.

Step 2: Feed The Internet

Meanwhile, another site, “Backyard Garden Lover” (yes, a gardening blog) ran the same headline about Papa John’s buyout.

That post then got scraped, cached, and re-shared across more than 100 other sites.

Why? Because suspicious news aggregators auto-syndicate and republish content in their networks. The more times a headline appears on the internet, the more likely Google search will index it.

Before long, a few legitimate financial outlets, like Bloomberg, noticed “multiple reports” of a Papa John’s buyout and wrote stories citing ABC Money as the source.

And suddenly, the stock was up 13%.

Step 3: Rumourville

The funny part is that sometimes real buyout rumours do start this way.

Rumours don’t need to be true. They just need to sound like something that could be true.

When that rumour reaches the right audience, especially traders, algorithms, or journalists, it starts behaving like information.

And if enough people trade it, it becomes true, at least temporarily.

Trading on rumours can be very profitable. That’s why a new rumour just has to look similar to things that were true in the past.

Rumour trading is not “rational” in the fundamentals sense.

It’s rational in the “I’ve seen this movie before” sense.

Step 4: Reality Intrudes

A few hours later, Papa John’s issued a statement: they had not received any buyout offer.

No deal. No bidder. No $2.7 billion.

But for a few hours, someone managed to make the rumour look just plausible enough.

Step 5: Let the Machines Cook

When a story like this breaks, two types of readers see it.

First, the humans. They read “Papa John’s” and “buyout” and think, “Huh, that’s interesting. I like pizza.”

Then, the machines see it. And the machines don’t think at all.

Most trading desks subscribe to automated headline feeds. Tools that scan financial news sites for words that historically move prices: acquisition, merger, bid.

When one of these bots spots “Papa John’s” and “$65 per share,” it doesn’t stop to ask why the scoop came from a gardening blog.

It just knows that “company + buyout + price” almost always = “stock goes up.”

So it buys.

That buying triggers a cascade—each new trader assuming the previous one must have known something real.

Don’t Eat the Clickbait

The moral isn’t “don’t believe what you read on the internet.” It’s maybe “don’t trade on what you read on Backyard Garden Lover.”

I’ve talked before about how attention flow is sometimes better than cash flow. Today, the easiest way to move a stock isn’t to change the fundamentals: it’s to simulate the news cycle for 15 minutes.

And for a few hours on Monday, that was enough to make Papa John’s worth hundreds of millions more.

Which tells you less about pizza and more about markets: markets will eat anything, especially when it’s served fast and looks kind of like a deal.

Hunterbook Media was the first to report this.